Back to Discontent?

Is this the second winter of discontent?

Huge waves of the public sector are on strike, prices are drastically rising and the standard of living is falling. The UK is in the grips of a financial crisis.

With Inflation reaching its highest level since 1980 and pay rises falling well below this level, it’s easy to see why workers are striking for higher wages and better conditions.

This situation does have undeniable similarities with the winter of 1978/79, when inflation soared and widespread strikes led to the downfall of James Callaghan’s Labour government. In turn, leading to the introduction of stricter trade union laws by Margret Thatcher’s government.

During this Winter of Discontent, more than twelve million working days were lost to strike action. This dwarfs today's disruption, with 1.6 million working days lost up to January 2023.

So, is the UK really in the middle of a second winter of discontent?

What was the winter of discontent?

The current cost of living crisis

The price of food and household bills have continued to rise, with gas prices rising 129% in the year to February 2023. Wages are not keeping up with this causing the standard of living in the UK to fall. It's hard to not be effected as inflation continues to rise.

Whats causing the crisis?

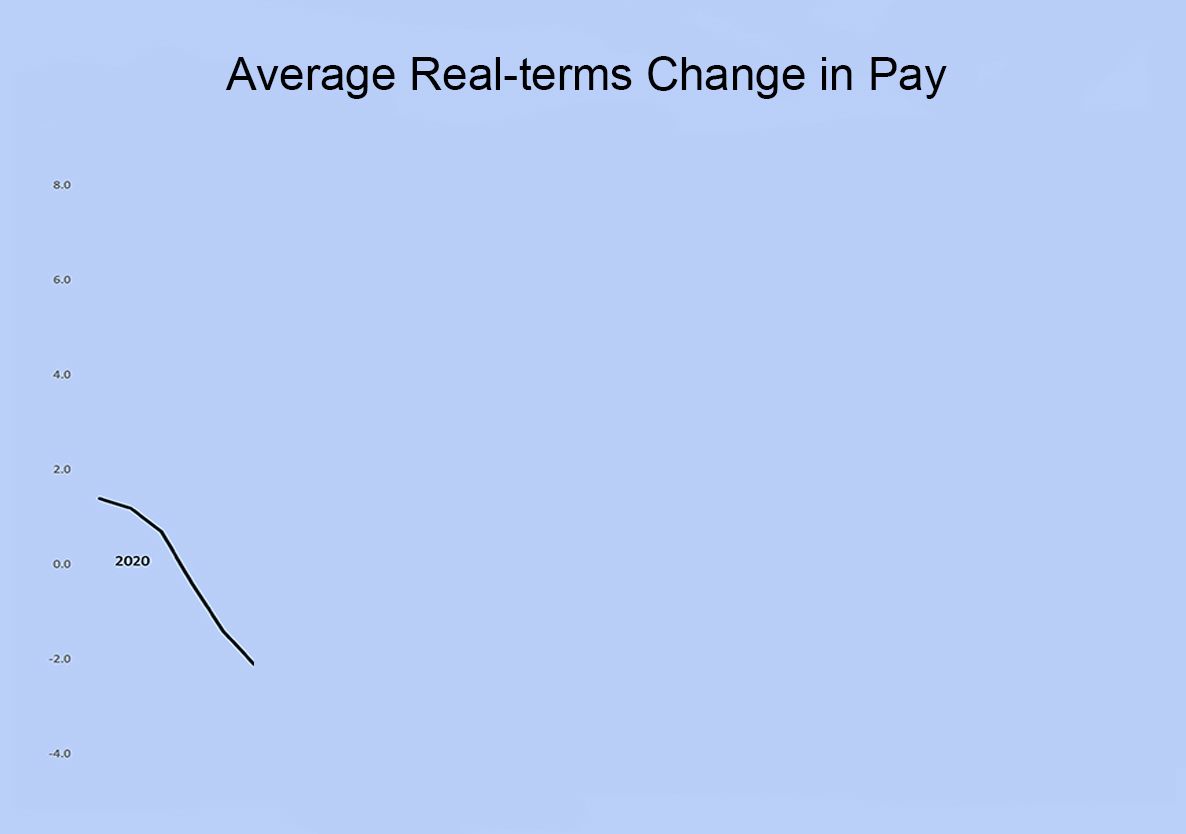

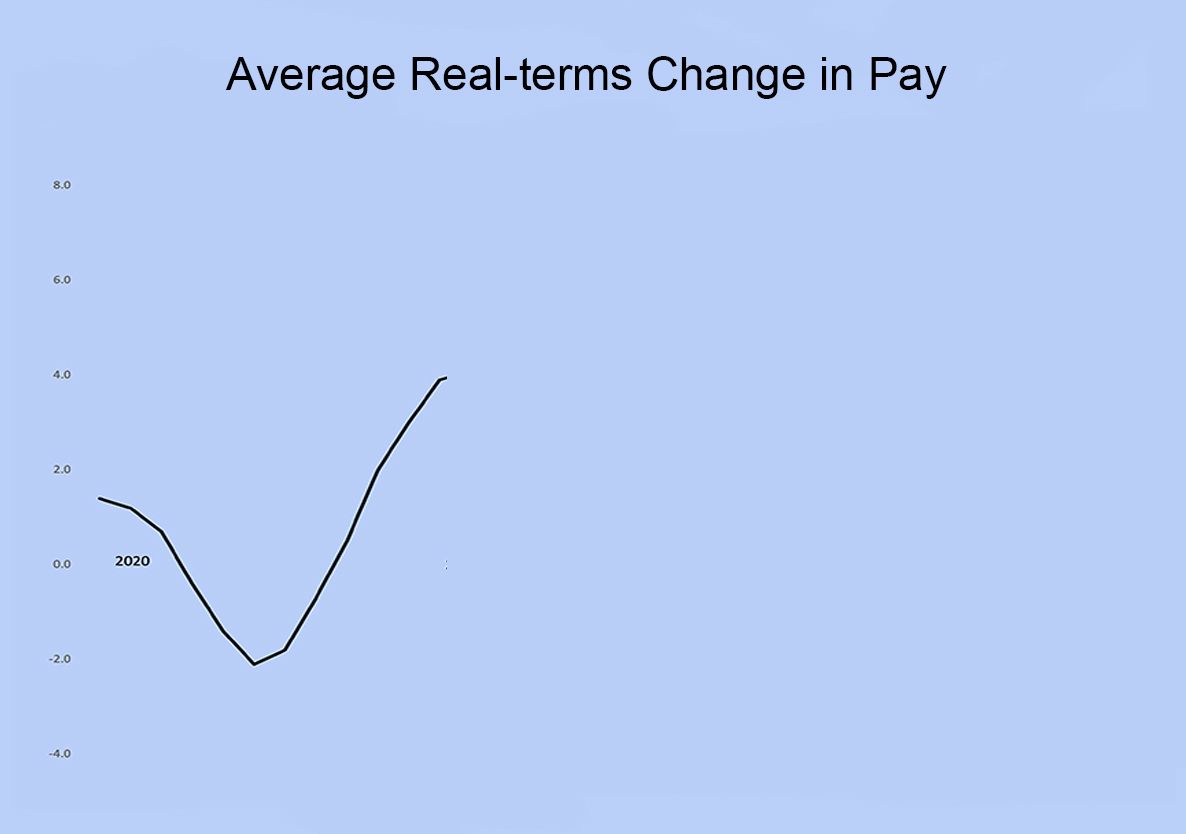

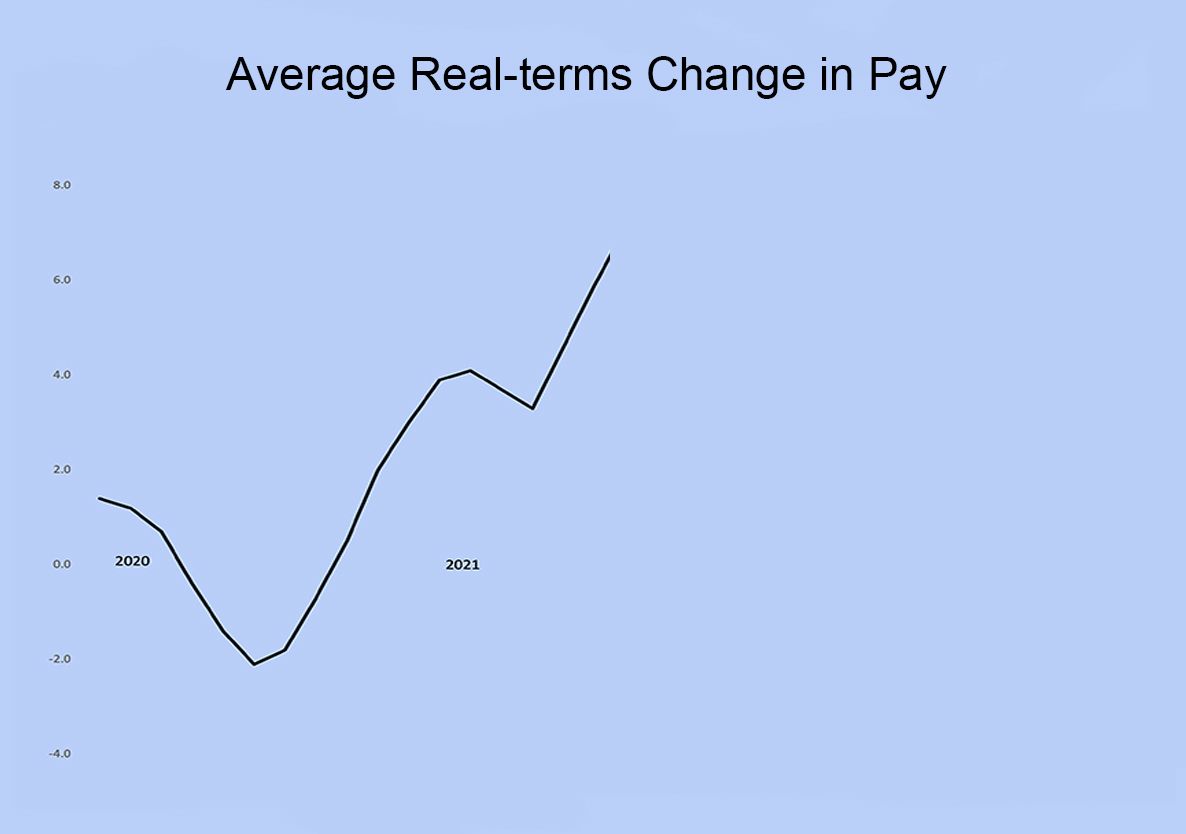

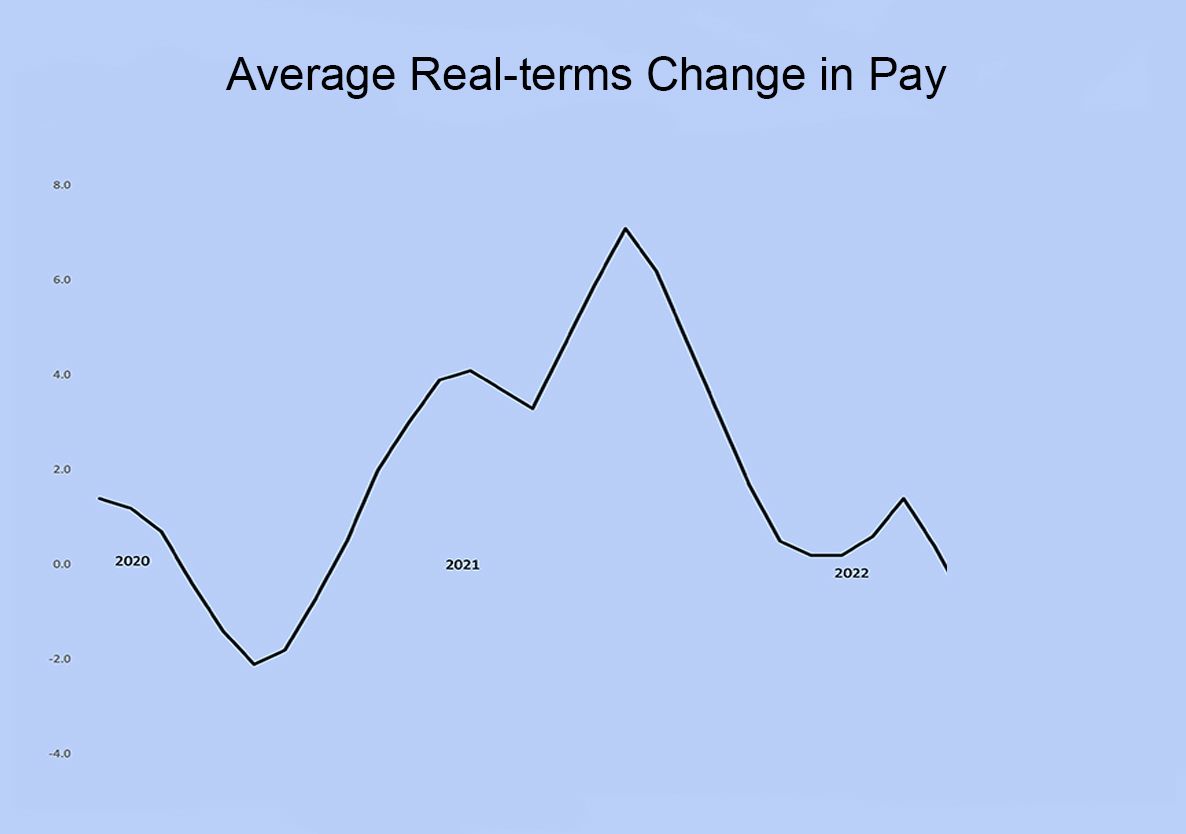

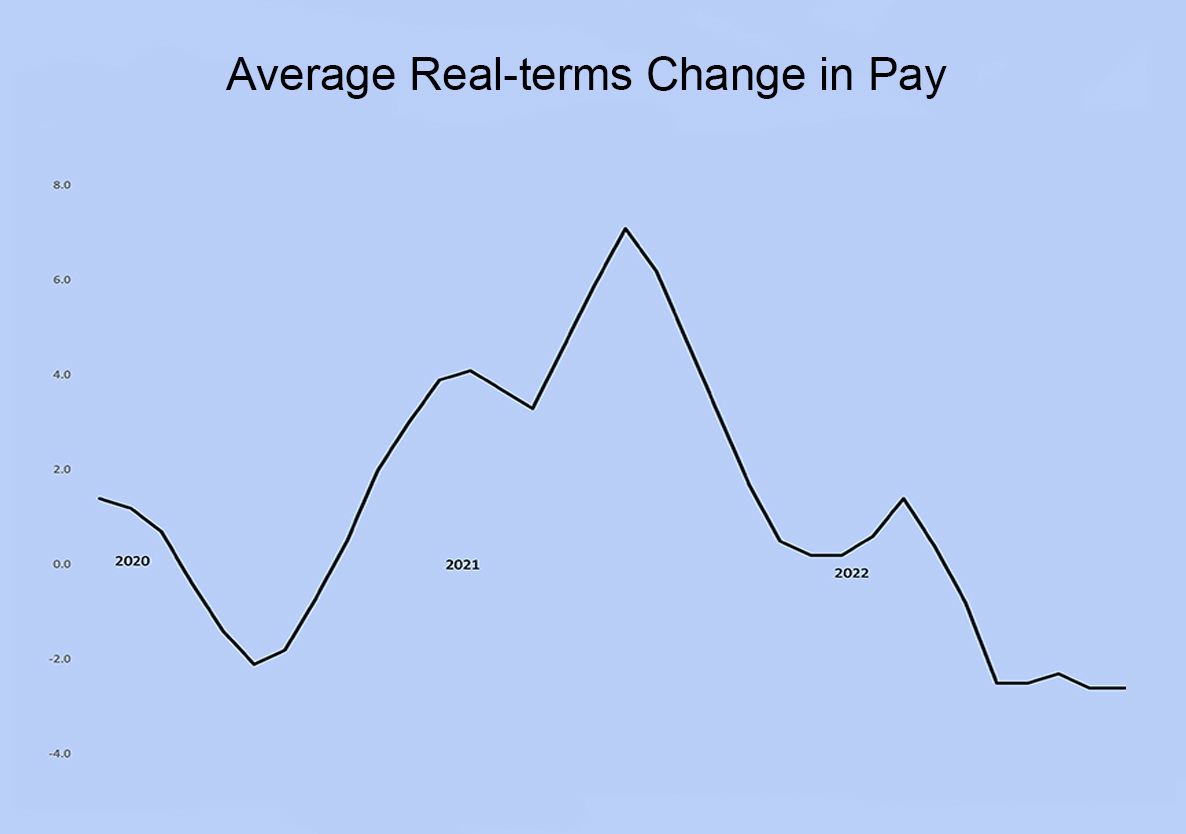

Average pay in the UK has failed to keep up with the rise in inflation. Real-term pay fell at it's fastest rate in 20 years, at the end of 2022, with public sector wages in particular falling well behind the private sector.

According to the Office of National Statistics, wages fell by 2.6% in 2022 when taking inflation into account.

Russia's invasion of Ukraine, in February 2022, and increases in the wholesale price of oil and gas has been blamed on this drive in inflation. Following the invasion western countries including the UK implemented a ban on Russian oil and oil products. However, underlying factors like Brexit and an increase in demand has also had an impact.

A protest calling for more cost of living support from the government, in February 2022

In response to public outcry, in May 2022, the UK government announced a package of measures to help support families with the rising cost of living. However, this package has widely been criticised; with over 50 faith, charity, trade union and organisational leaders signing an open letter to the Prime Minister saying the support, "whilst welcome, hasn’t gone far enough".

Here you can see the trends in wage growth and Inflation since 1975.

Inflation during and before the Winter of Discontent rose to over 18%

This dwarfs even todays figures, reaching almost double figures.

However, in the late 1970s wide spread strikes led to an increase in average wages, reaching higher than inflation.

In contrast, pay in the present day hasn't kept up with inflation despite fierce union action.

Strikes have been most wide spread in the public sector where pay is significantly lower than the private sector.

Sophia's story

The children charity Banardos reports more than 1 in 4 children in the UK currently live in poverty, it is apparent that families are being hugely effected by the cost of living crisis.

Mother of two, 32 year old Sophia Lister from West Yorkshire opens up about the struggles she and her family are currently facing. Stating that she is "having to cut back on essentials... I am finding it hard to feed my children".

Acknowledging the mental strain caused by the crisis, Sophia talks about having to spend less time with her children due to "having to put extra shifts in at work to cover bills... It's not fair on them" she states.

The full time Associate Ambulance Practitioner talks about "struggling to afford to get to work". Like many Britons, this has led her to cut back on non essential car journeys. According to the ONS 42% of people are cutting back on non-essential journeys. This is reality for Sophia.

Working for the Ambulance Service, Sophia addresses the fact that her "salary is not keeping up with inflation". However, despite taking part in recent strike action she addresses the struggles of "missing a day's pay" on these days.

Like the rest of the UK, Sophia is receiving the government's cost of living support. Although she acknowledges the difficult situation, she does agree with the criticism of the government. "[The government support] helped to a certain extent but they could do a lot more".

Megan's story

Students are often ignored especially throughout the cost of living crisis however they are affected disproportionally due to student loan payments which during the 2022-2023 academic year only increased by 2.8% while inflation is nearing 10%. Meaning for many student loans don't cover the basic day-to-day living costs. Almost half of all students admit to missing lessons to go to work.

21-year-old, Megan Monk, a third-year BA Photojournalism student at the University of South Wales, has noticed a drastic increase in the price of everyday essentials. "Just for a pint of milk the price has gone up. I used to be able to get a litre for 90p and now I'm paying £1.10.... It all adds up".

Despite receiving the maximum student loan amount of £9,706 Megan talks about how "it still isn't enough to keep up with the constant increase in prices... I'd say I'm lucky with my student loan but even that doesn't cut it. I strictly budget my money to make sure it lasts".

Like many students, she has been forced to get a part-time job. "I work a part-time minimum wage job alongside my university studies just to make ends meet. This affects my studies and gives me less time to complete submissions because I have to work to pay rent and food... Minimum wage isn't enough to live on".

Government cost of living support for students is lacking. Megan agrees the government support hasn't gone far enough: "I personally can't say I have had any support from the Government. I know some of my family members have and even then it doesn't go far enough".

Megan has taken several cost-cutting measures, just to afford the essentials. "It costs around £10 to wash and dry" her clothes in her student accommodation building. "Washing your clothes every week leaves you without £40 a month which could be used for food and towards rent payment... I now hand wash all my clothes... just to keep the cost down".

Splott's Breakfast Club

All of this has led to a huge rise in people asking for help from food banks. According to the Independent Food Aid Network, almost 90% of food banks surveyed reported increased demand in December 2022 and January 2023. One example of this is Splott's Breakfast Club, in Cardiff.

Run by Splott Community Volunteers, the club helps up to 100 people every week. "We provide for people who are in food poverty... and just help people muddle through this crisis"

The amount of people using The Breakfast Club has been gradually increasing in recent times according to Angela Bullard, the co-founder of the organisation. "It's been manic sometimes but people are desperate," she says.

The organisation has been a lifeline for people like Beverley Gill, who has just retired and supports her family. "I have a grown-up family but also grandchildren, who I support, which can be quite expensive," she says.

Beverley states, "We started coming to this community about six years ago" to meet new people however, she points out that the need in the community has increased. The centre gets "crowded" she says.

Addressing the increased demand, Angela says the local government "have recognised the need and are allowing us to move into one of their bigger buildings so we can provide more breakfast clubs and open for longer periods of time". Angela continues "but I think the government itself really need to step up more"

Others, like Jacqui Crawley, come to the centre to socialise with others and support those in need. "I'm not really feeling the pinch," Jacqui says "but I know other people are and the only way to support it is to come".

What are the strikes about?

As more and more people join strike action across numerous industries, with tens of thousands more expected to join, the UK continues to be effected by disruption.

But what are these strikes really about…and can we draw any parallels with the Winter of Discontent?

One union that is intensifying their pay dispute is the University and College Union (UCU). The union is claiming their pay has been cut by 25%, when considered in line with inflation. Calling for "a fair pay deal", the elimination of casual workers in the industry and action on work loads, the UCU called 7 weeks of strike action and a marking boycott. According to Terry Driscoll, the University and College Union (UCU) rep for the University of South Wales, "Compounding the problem for us is this is in a situation where the university sector is making record profits."

"For the public sector, they've lost the equivalent of 25% of their wages since 2010. That's not sustainable."

Another sector that is striking is healthcare. This wave of strike action has effected the NHS greatly. With nurses, ambulance workers and junior doctors heading for the picket lines it's hard not to notice their calls for better pay and working conditions. For paramedics like Jamie Stone, who works for the Welsh Ambulance Service, the real issue is how they continue to look after their patients. "We're not able to continue caring for patients anymore in a reasonable manner" Jamie says, as he call for a "change in the process of care". Waiting times across the NHS have risen with category two emergencies waiting an average of 93 minutes for an ambulance, at the end of 2022. "The system is broken, the system needs to be repaired" says ambulance worker Ian Price.

"People are dying, people are dying every day of the week"

The problem is also evident for nurses, who are striking to demand a pay increase. "Theres just no incentive for some people to stay in the job" says striking nurse, Andy McDougall "The biggest problem for me is the staff shortages". There are over 43,000 nurse vacancies in England alone adding to the crisis in the NHS.

Today's wide spread strike action does have undeniable similarities to the Winter of Discontent. Similarly to the 1970s, unions today are calling for above inflation pay rises. However, unlike the seventies, disputes are a lot more complicated with many calling for changes in working practice and better conditions, especially in the NHS.

Why are the strikers protesting?

Picket lines are a big part of striking, with workers standing outside their place of work to tell others why they are striking. Picketers often hand out leaflets and chant to spread the word.

A picket line is a boundary established by workers on strike. The workers often stand on the picket line in protest.

As members of the public pass picketing doctors at an unusually loud hospital entrance in Bristol, striking junior doctor Zoe Brunswick says "It's also a chance to talk to the public... and correct some of the myths that the public might think". While junior doctors are calling for a pay rise of 35%, the British Medical Association claim this is simply pay restoration. 175,000 planned hospital appointments and procedures were postponed during the BMA March Strike. "We don't want to be here on the streets" says junior doctor Emma Coombe, "we want to be in this hospital caring for our patients".

"We're here on the picket line in protest really at a government that so far has refused to negotiate with us"

At the Trade Union Congress's (TUC) 'Support the Strikes' rally, unions came together to support striking workers. Held on budget day, in front of the UK government building in Cardiff, the crowd joined in chants of "Support the strikes" while speakers addressed the gathering. Jason Richards, a branch secretary for the Communication Workers Union (CWU), highlights the importance of public demonstrations. "With the attacks on the workers across the country I think it's so important that, as a movement, we stick together and show solidarity".

The Public and Commercial Services union (PCS) Nation Officer for Wales and the South West addressed the crowd outside the building. Encouraging unions to unite he told me "we can get the government to back down if we are united and we apply pressure through industrial action".

"We have to send a message to the UK government. We have to tell them that enough is enough, and that we need more money"

Student nurses Tuscany McCraw and Anya Dunne are standing with members of the Royal College of Nursing at a picket line in Bristol. As the group cheer when cars beep in support, Tuscany says "it's time to stand for what's right and get the pay that we deserve".

These scenes look eerily similar to that of the 1970s. With picket lines stretching outside workplaces and protests effecting the government.

The Minimum Service Levels Bill

On the 16th of January 2023, MPs voted in favour of The Strikes Minimum Service Levels Bill. The legislation, which is currently still stuck in the House of Lords, could force public service industries to keep a minimum service level on strike days. This level will be set by the government.

The suggestion of this bill has been extremely controversial, with the Trade Union Congress (TUC) organising a national 'protect the right to strike' day on the 1st of February. As 84 rallies took place across the UK and a number of industries coordinated action, union members once again took to the streets demanding a halt to the legislation.

At a rally in Central Square in Cardiff, union members joined with members of the public outside the UK Government building. The building is home to the Welsh office of the Secretary of State for Wales and was met by chants of "Tory's out" and "hands off our rights".

Jason Richards, a branch secretary for the Communication Workers Union echoed the views of most union leaders. He told me "The Strikes Minimum Service Levels bill... undermines the trade unions and worker's collective action".

While speakers addressed the packed square, Sian Gale the skills and development manager for the BECTU union told me "If we want to withdraw our labour, then we should have the right to do so".

The general secretary of the Wales TUC, Shavanah Taj, claimed that the government "are attacking our democratic right to stand up". She believes they should instead be "actually sitting down with unions and finding a way forward, finding a resolution to all of this".

Kwebena Devonish, a stand-up to racism campaigner, attended the Cardiff rally to stand in solidarity with striking workers. "It just shows how afraid the government is of collective action and collective power".

Kwebena compares this bill to the anti-union laws introduced by the controversial prime minister Margaret Thatcher. In response to the mass strike action seen during the winter of discontent, Thatcher introduced major restrictions on the power of trade unions and the right to strike. This anti-union government sentiment can clearly be compared to what is happening today. This is evident on the famous Mirror headline "Crisis? What Crisis".

With cancelled trains, missed hospital appointments and schools closing it's hard to find someone who hasn't been affected by the strikes.

2.5 million working days were lost between June and December 2022. This is a huge number, however, it pales into insignificance when compared to the winter of discontent where 29.5 million working days were lost through a similar disruptive period of time. Inflation today has also hit its highest levels in over 40 years, with recent figures being over 9%, but is dwarfed by the figures from the late 1970s when inflation reached over 18%. What is clear to see are the similarities in the government's response, such as the Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Bill and Margeret Thatcher's anti-union laws. While images from picket lines and protests are definitely comparable.

Despite comparisons perhaps being slightly overstated, it's important to not downplay the significance of the current situation; food bank usage is up, food and energy prices are rising, wages are generally stagnant and workers are once again taking to the streets. It’s clear that the country is struggling and that for many the UK is back to discontent.